Parsing through the individual elements and ingredients of a movie to investigate the meaning and themes behind it can be fun and rewarding, one of the key reasons I wanted to start jawing about movies here in the first place. But it’s very easy to go too far, to make unfounded assumptions about a filmmaker’s intentions and project concepts and interpretations that were never intended. Just as a viewer going into a film looking to hate it will probably find ample reason to feel that way upon watching it, someone who sees a film believing it will validate a particular point-of-view will probably see plenty of evidence to back up those views, whether it exists or not.

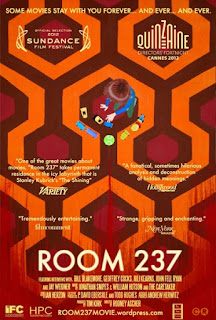

This pitfall is the focus of the unorthodox documentary Room

237, which offers a platform for several fans of Stanley Kubrick’s mysterious

and unsettling film adaptation of Stephen King’s novel The Shining to present

their unique interpretations of the film’s deeper meanings. What for many

viewers is simply a creepy movie about a family trapped in a haunted hotel becomes

a multitude of things for others, including a stand-in for

cultural traumas, an expression of Freudian concepts and confirmation of

outlandish urban legends.

The films of Stanley Kubrick lend themselves well to the type of obsessive analysis this documentary’s commentators present; he was an incredibly brilliant individual known for intense research, meticulous planning and very deliberate execution when it came to his films. He exerted total control over every single aspect of them and thus every element is assumed to be there for a very specific reason and hold some important significance. With The Shining, there also seems to be an unspoken assumption that a filmmaker of Kubrick's stature wouldn't choose to work in such an ignominious yet popular genre as horror unless he was using it to expose some carefully concealed agenda to the unsuspecting masses. The fact that Kubrick has died and is therefore in no position to refute any of these theories (not that he would have while alive anyway) certainly helps.

But I doubt he would have endorsed much of the speculation presented here, most of which involves extrapolating dubious ideas from seemingly trivial details such as set dressing, shot composition and random artifacts of editing. The imaginative theories that result from this form of intense cinematic investigation range from arguable (the film is really about the slaughter of native Americans and how the collective guilt of such atrocities affects the present) to being outright delusional (Kubrick was using The Shining to make a veiled confession about his involvement in faking footage of the Apollo moon landing).

With such a heightened sensitivity to the film’s details, things

quickly get blown out of proportion. The presence of the number 42 in the film

somehow signifies its connection to the Holocaust (of course sci-fi readers know there

are much more important connotations to this number). The big-wheel joyrides of

little Danny Torrance become a symbolic trip through the planes of

consciousness into the darkest secrets of his parents’ psyches. By the time we

see the visually arresting but seemingly meaningless results of someone who

decided to play the film both backwards and forwards simultaneously, it becomes

clear this is a lot less about Kubrick’s cinematic intentions than what the viewer

wants and needs to take from it.

The multimedia analysis includes copious footage from The Shining and other Kubrick films, often slowed down, intercut or superimposed to suggest synchronicities and parallels, all of which serve to remind us of the seductive visual allure his films offer and make us appreciate the temptation to look closer. The fun surprise is that for all the entertainingly bizarre content, there are a few sharp insights. One speaker presents detailed maps of the film’s sets that show their geography makes no sense and notes how Kubrick structures shots that seem to deliberately point up these logical inconsistencies. Another illustrates Kubrick’s tendency to allow seemingly deliberate continuity errors in his films, generally interpreted as a way to keep viewers subconsciously off-balance. Still another points out the odd and funny detail that Jack Nicholson’s character is reading an issue of Playgirl magazine while waiting to see the hotel’s manager. All of these touches are clearly deliberate choices on Kubrick’s part, but what, if anything, do they mean?

When the participants start promising to demonstrate the presence of other, more revealing details, we’re interested. There’s great build-up in several moments as the film is slowed down frame-by-frame with the promise of an amazing revelation coming in just a moment if we watch closely enough. That anticipation is generally rewarded with an anti-climactic assertion that’s usually so ludicrous we’re both amused and embarrassed by the fact that we’ve been pulled to the edge of our seat, peering at the screen in the hopes of learning some solution to a puzzle we didn't realize we wanted solved.

Although the goal of the film would seem to be less about measuring the validity of these theories than investigating the mindset of those who conceive of them, director Rodney Ascher takes a very hands-off approach. Aside from some sly choices regarding which film clips accompany the narration, he doesn’t provide much in the way of commentary on the theories or those presenting them but merely allows them to explain and illustrate their various points. We never get to see their faces of the participants or learn much about their identities beyond their names.

On the one hand, it’s refreshing that Ascher does not pass judgment or hold them up to ridicule, which would seem to be the easy and obvious approach. On the other hand, the approach has drawbacks, as it becomes difficult to distinguish each disembodied speaker until their comments lead back to their individual theory, and more importantly, we get no context for their interpretations. Contrast this with the style of say Werner Herzog, who can present the beliefs and views of his subjects at face value while indulging his clear fascination with the people themselves.

That said, the theories do offer some insights

into the psychology of the obsessive film viewer, particularly those given by Jay

Weidner, who promotes the Apollo 11 theory here. He haughtily informs his conclusions are self-evident to anyone really paying attention. We find ourselves confronted with similarities

in the mindsets of the film critic and the conspiracy theorist in that both

have the somewhat egocentric conviction that they alone grasp the true meaning

of things because they’ve been able to observe the clues that everyone else

missed.

As someone who spends a lot of his time watching movies

trying to find all these meanings and themes, I should probably feel offended

or at least insecure about the depiction of such efforts here but somehow I can’t.

Perhaps it’s the playfulness that Ascher manages to quietly inject into his

presentation or perhaps there’s the admittedly less wholesome reassurance that

the ideas being presented are much further out there than anything I could ever come

up with, but somehow the whole endeavor instead instills me with enthusiasm for

reading between the frames and trying to solve the riddles.

That brings us to the big question: what’s in Room 237, that

mysterious place that the evil seems to emanate from in The Shining? A

particularly apropos clip has Scatman Crothers answering the question quite

flatly: “Nothing.” However, I think a bit of the wit and wisdom of Yoda sums it up

even better: “Only what you take with you.” Watching the film, I felt my own

theory forming, my own take on exactly what Kubrick intended with the strange

ambiguities, non sequiturs, and riddles strewn about his filmography. I think

he did it to keep us guessing, to keep us studying his movies, to keep us talking

about them throughout the long unspooling of history. If so, then Room 237 is

Stanley Kubrick’s final vindication.

No comments:

Post a Comment