Growing up in the New England area during the early 80s, one of my purest joys would come every Saturday afternoon when Creature Double Feature would air on channel 56. There would be three hours of classic monsters from the Universal years, the Hammer cycle, the cheapo epics of AIP, and best of all, those deliriously colorful imports from Japan that introduced the world to such titans as Godzilla, Mothra, Rodan, and Gamera. Although giant monster movies had been around since as far back as the silent film version of The Lost World, it was from Japan that the genre earned its name: 'kaiju,' meaning 'strange creature,' although the most accurate form for our purposes would be daikaiju, or 'giant creature.'

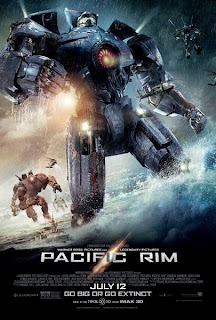

There was a primal, gleeful joy in watching giant dinosaurs, gorillas, insects, crustaceans, and the like smash through model landscapes or wrestle each other in cataclysmic battles to the death. Watching Pacific Rim, you can picture director Guillermo del Toro cackling with that same excitement during every jumbo-sized set-piece. One of the few filmmakers who really deserves to be described as a visionary, he's conceived of some of the most beautiful, fully-formed worlds of fantasy the movie screen has ever seen and populated those worlds with flawed, identifiable people struggling with their own problems and needs. Never before has he been able to engage his feverish imagination on such a colossal scale and while the results bring back the fun of those Saturday afternoons, this time the human story tends to get crushed underfoot.

In fact quite a few people are being squashed, as a strange dimensional tear at the bottom of the Pacific Ocean unleashes ridiculously gigantic monsters to attack coastal cities. In response, the governments of the world unite to develop the Jaegers, a fleet of giant robots driven by pairs of pilots to exterminate the gargantuan menace. Following a particularly brutal battle that cost the life of his brother and co-pilot, Jaeger ace Raleigh Becket (Charlie Hunnam) has had enough of the fight. But as the increasing number and size of the creatures overwhelm his mechanized forces, Becker's former commander Stacker Pentecost (Idris Elba) brings him back to man one of the last remaining Jaegers alongside specialist Mako Mori (Rinko Kikuchi) in a last, desperate gamble to end the earth-shaking invasion once and for all.

The first thing that hits us is the care and thought that del Toro puts into his world-building. He takes the basic premise of the kaiju genre and has fun coming up with what some of the social effects of such events might be; the skeletons of defeated kaiju become part of the urban landscape, eventually being integrated into architecture; Jaeger pilots become the new superstar athletes, with teams from different nations out to prove themselves the most effective; policy debates rage over the effectiveness of the Jaegers and whether it would be more cost-effective to build a defensive wall around the coasts. All of these strange little details add to the verisimilitude of the world onscreen.

With so much consideration given to constructing the world, it's a bit jarring how broadly-drawn the people inhabiting it are. Almost everybody fits into the standard archetypes of military dramas: the emotionally-wounded hero; the eager rookie; the hard-ass commander; we even get the condescending rival in the form of Australian Jaeger pilot Chuck Hansen (Robert Kazinsky) channeling Kilmer's Iceman attitude. To be fair, emotionally-profound characters aren't the primary draw to kaiju movies. As a kid, I was usually impatient to get the talking parts over with so we could get to the monster fights, so perhaps using well-worn clichés is another way that del Toro is paying homage to the films he grew up with. But considering so much of the movie between those monster fights is spent getting to know these characters, you'd think they'd feel a bit more dimensional and interesting.

It's especially odd since del Toro and screenwriter Travis Beacham invent the perfect narrative tool to accomplish this: the concept of "drifting," a telepathic link required by Jaeger pilots to share the mental strain of controlling a hundred-foot-tall robot. While its main purpose is to allow each pilot to manipulate one side of the machine, ensuring that the left hand does in fact know what the right is doing, it also forces the pair to share memories and emotions, a by-product that has tremendous dramatic potential to dramatize and comment on the growing relationship between the lead characters, the intense connections that form between fellow soldiers in combat and the merging of humankind and its technology.

Unfortunately the idea of drifting doesn't feel as well utilized or thought out as many of the film's other details. The rules of how it's supposed to work are foggy and inconsistent. We're told that the pilots' minds are linked to the point where they share thoughts, and yet they still speak to each other verbally and there are several points where one does something in a battle that surprises the other. But more importantly, there's little exploration of the intimacy it would force Mako and Raleigh to share or how it would affect their relationship. Instead it's mostly used as a handy visual way to reveal character backstory, particularly Mako's, and in doing so also reveals one of the biggest shortcomings of the script by introducing internal conflicts for the two leads that are never resolved. Raleigh and Mako's attempt to drift together unleashes flashbacks of the traumas that are supposed to inhibit them, but there's no point at which we see them taking steps to overcome this emotional baggage. These ideas are dropped as soon as it becomes time for a big monster fight.

Take Raleigh; clearly he's supposed to be haunted by the death of his brother, even more so since he was still connected to him in the drift, sharing his fear and pain as he died. Yet we never really get a sense of his process of moving on from the loss. He gives a speech about his inability to let people in, but this doesn't align at all with Raleigh's behavior in the film or his relationship with Mako. These problems are exacerbated by Hunnam's curiously flat performance. I haven't gotten around to seeing Sons of Anarchy yet (I'm way behind on my TV watching) but have seen Hunnam in enough movies to rate him as a decent actor. Thus it's surprising to find he doesn't really connect in the role, failing to convey Raleigh's grief and turmoil and delivering every line in the same bland, gravelly drawl.

Kikuchi is more successful as Mako, letting us see the strength in her eyes while suggesting the vulnerabilities hidden behind them, yet the character never feels as active as she should. While the nature of "drifting" naturally limits her independence, at least in the action scenes, for much of the plot Mako's choices seem to be dictated by Raleigh and Pentecost. You'd think driving around a hundred-foot tall robot would be a bit more empowering. Similarly to Raleigh, much is made of how her psychological damage would make her a liability in the field and is portrayed as a significant danger in one suspenseful scene, but as the third act stomps closer, this plot point is cast aside without any further mention.The supporting cast gets to have a bit more fun, tearing into the cartoony nature of their roles with abandon, particularly Charlie Day and Burn Gorman as the corps' crackpot scientific advisers. Day could almost be playing a stand-in for the average kaiju fan with his childish enthusiasm about the beasties; he's utterly fascinated by the idea of monsters the size of buildings but doesn't have enough first-hand experience to fear and respect them as he should. Between his rash scientific methodology and Gorman's hilarious stodgy and twitchy stubbornness, they both seem like caricatures of American and British stereotypes, and yet they manage to have character arcs that feel more complete than our heroes. Ron Perlman, a del Toro mainstay, growls through his fun turn as a black market gangster dealing in kaiju tissues and organs, and Clifton Collins Jr. lets his flamboyant wardrobe and hairstyle do most of the work for him as a Jaeger technician.

But the real stars of the movie are the robots and the monsters and it's during their confrontations that Pacific Rim really finds its happy place. Plot problems and script deficiencies fall away when we're treated to the spectacle of the Jaegers and kaijus squaring off through cities, at sea and under it. There's a comic book mentality to the battles, as the machines all have their own gadgets and signature moves, including missiles, swords and rocket-powered punches, while each monster has its own unique abilities as well. While the monster designs lack the diversity of their classic Japanese counterparts, with each one some variation of a bulky, knobby-faced reptile, they are nonetheless impressive and they always register as a genuine threat to our heroes.

In a summer filled with destruction and the casual destruction of innocent people, it's also refreshing that a bit more attention is paid to the civilians on the ground level. Once the alarm sounds, people stream into the shelters not with the frenetic panic common to Godzilla movies but the weary, practiced bustle of a population that has grown accustomed to kaijus as another fact of life. It's not only another facet of the film's reality but seeing them find safety underground makes it a bit easier to enjoy the wholesale devastation that follows.

The centerpiece battle, a garishly neon-lit romp through Hong Kong with the combatants battering each other with ships and smashing each other through buildings, illustrates the gorgeous visual palette of the whole show. As the photos above demonstrate, the movie is bathed in gloriously vibrant colors, again suggesting the influence of comic books and creating an aesthetic that matches the often broad tone of the production. This is also complimented by the score from Ramin Jawadi, probably best known for his infectiously epic opening theme to Game of Thrones. The heroic march mixes orchestral pomp with an undertone of rock guitar that reflects the story's fusion of grandiosity and fun.

Perhaps with the first part of this review I'm holding del Toro to the same kind of unrealistically high standards I mentioned in my Monsters University review regarding the perception of Pixar movies. If so, it's a testament to the high quality of his filmography and a reflection of how much I wish the movie could be as dramatically satisfying as it is fun. A bit more attention to the human side of things would have left Pacific Rim as an unmitigated masterpiece, rather than just the incredibly enjoyable monster movie that it is. At least there's still hope on the horizon that the return of a certain kingly monster will give us the ultimate kaiju flick that Pacific Rim comes so very close to being.

Ok, so thus endeth the review, now begins the discussion. What did you think? Agree? Disagree? Did I miss something worth mentioning? Leave your comments below.

No comments:

Post a Comment