(Obviously these first few entries are coming a bit late, as the multitude of local October events have left me a bit preoccupied.)

Ok, a creepy story for you and it's completely true... no, honestly... well, mostly true, names changed and all that... well, part of it is probably true... if you don't believe me, ask anyone who lives in The Town That Dreaded Sundown.

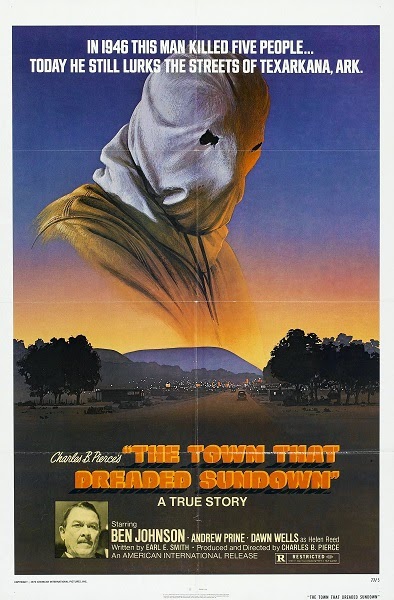

Independent filmmaker Charles Pierce had a diverse career in Hollywood. Amid decorating sets for productions such as The Outlaw Josey Wales and co-writing the Dirty Harry film Sudden Impact (Pierce took credit for Eastwood's classic "Go ahead, make my day" line), he also pioneered the strange little genre of docu-horror.

His debut film, The Legend of Boggy Creek, was a dramatization of sightings of a Bigfoot-like monster in Arkansas. For his follow-up he delved into another creepy bit of Arkansas lore, a series of attacks in Texarkana by a masked maniac who victimized couples by night. The resulting film has some potent moments of terror, but is dragged down by some horrific tonal inconsistencies.

Narration by Vern Stierman (the same voice of authority Pierce used for Boggy Creek) paints a portrait of 1940s Texarkana as a idyllic Midwestern town slowly returning to normal after the close of World War II. That normalcy is destroyed when a couple parked on a lovers' lane is assaulted by a hulking figure wearing a sack mask who beats them viciously and bites his female victim. Before long, the perpetrator, nicknamed the Phantom Killer, has struck again and graduated up to murder.

With the local police out of their depth, legendary Texas Ranger J.D. Morales (Ben Johnson) is brought in to take over the case. Teaming with deputy sheriff Norman Ramsey (Andrew Prine), the men race to discover some clue to the killer's identity as his crimes become bolder and the town's population begins to panic.

It's strange viewing this movie in the shadow of the slasher films that would spring up in its wake and doubtlessly take some inspiration from it. The appearance of the killer himself suggests an influence on the first bag-headed appearance of Jason Voorhees as well as similar headgear for psychopaths in The Strangers and Nightbreed. As played by stuntman Bud Davis, he convinces as a terrifyingly authentic human monster and the scenes depicting his crimes as presented in a suspenseful but tasteful manner, barring one rather colorful use of a trombone.

So it's jarring that Pierce alternates these set-pieces with clunky comedy bits involving a scatter-brained patrolman (played by the director himself) that feel as though they've careened in from a Dukes of Hazzard episode and disrupt the momentum of the story. The overuse of narration also becomes more jarring as the film progresses, making explicit what the visuals playing beneath do an adequate job of conveying on their own.

Once he strides into the film, Johnson brings with him the gravitas of his background in Westerns to suggest the kind of frontier gunslinger audiences could count on to set things right, making it all the more unsettling when he finds his efforts to snag his quarry continually frustrated. As much as he may seem an old school lawman, it's refreshing that he isn't a bull-headed tough guy but is open to ideas from his subordinates and, in a particularly progressive moment, consults with a prison psychiatrist (Earl E. Smith, giving possibly the film's second-best performance after Davis) who ominously warns that their suspect is way ahead of them.

Prine, who I'd come to know best as the evil Visitor commander Steven from V, conveys a lot about his sharp-witted cop just through body language. Following the first crime, his anxious stance and wandering eyes betray how beyond his experience this incident is. Yet Ramsey keeps pace with Morales and the two make an effective team. Interestingly, Prine also takes credit for writing the film's exciting finale, in which Morales and Ramsay give chase to the Phantom Killer through a sand pit.

The liberal mixing of fact and fiction gives the story an added edge, particularly since (SPOILER), the Phantom Killer was never apprehended, leaving audiences of the period with the lingering question of whether the murderer was still out there, perhaps in the same auditorium as they were, watching his story unfold on the big screen. As such, The Town That Dreaded Sundown not only presages the questionable use of the 'based on true events' label for many modern horror films and the verisimilitude many found-footage flicks strive for, but also served as a model for higher-quality fact-based thrillers such as David Fincher's Zodiac, which features some very similar attack scenes and a similarly ambiguous resolution. A meta-sequel to the film is due out this month.

Ok, a creepy story for you and it's completely true... no, honestly... well, mostly true, names changed and all that... well, part of it is probably true... if you don't believe me, ask anyone who lives in The Town That Dreaded Sundown.

Independent filmmaker Charles Pierce had a diverse career in Hollywood. Amid decorating sets for productions such as The Outlaw Josey Wales and co-writing the Dirty Harry film Sudden Impact (Pierce took credit for Eastwood's classic "Go ahead, make my day" line), he also pioneered the strange little genre of docu-horror.

His debut film, The Legend of Boggy Creek, was a dramatization of sightings of a Bigfoot-like monster in Arkansas. For his follow-up he delved into another creepy bit of Arkansas lore, a series of attacks in Texarkana by a masked maniac who victimized couples by night. The resulting film has some potent moments of terror, but is dragged down by some horrific tonal inconsistencies.

Narration by Vern Stierman (the same voice of authority Pierce used for Boggy Creek) paints a portrait of 1940s Texarkana as a idyllic Midwestern town slowly returning to normal after the close of World War II. That normalcy is destroyed when a couple parked on a lovers' lane is assaulted by a hulking figure wearing a sack mask who beats them viciously and bites his female victim. Before long, the perpetrator, nicknamed the Phantom Killer, has struck again and graduated up to murder.

With the local police out of their depth, legendary Texas Ranger J.D. Morales (Ben Johnson) is brought in to take over the case. Teaming with deputy sheriff Norman Ramsey (Andrew Prine), the men race to discover some clue to the killer's identity as his crimes become bolder and the town's population begins to panic.

It's strange viewing this movie in the shadow of the slasher films that would spring up in its wake and doubtlessly take some inspiration from it. The appearance of the killer himself suggests an influence on the first bag-headed appearance of Jason Voorhees as well as similar headgear for psychopaths in The Strangers and Nightbreed. As played by stuntman Bud Davis, he convinces as a terrifyingly authentic human monster and the scenes depicting his crimes as presented in a suspenseful but tasteful manner, barring one rather colorful use of a trombone.

So it's jarring that Pierce alternates these set-pieces with clunky comedy bits involving a scatter-brained patrolman (played by the director himself) that feel as though they've careened in from a Dukes of Hazzard episode and disrupt the momentum of the story. The overuse of narration also becomes more jarring as the film progresses, making explicit what the visuals playing beneath do an adequate job of conveying on their own.

Once he strides into the film, Johnson brings with him the gravitas of his background in Westerns to suggest the kind of frontier gunslinger audiences could count on to set things right, making it all the more unsettling when he finds his efforts to snag his quarry continually frustrated. As much as he may seem an old school lawman, it's refreshing that he isn't a bull-headed tough guy but is open to ideas from his subordinates and, in a particularly progressive moment, consults with a prison psychiatrist (Earl E. Smith, giving possibly the film's second-best performance after Davis) who ominously warns that their suspect is way ahead of them.

Prine, who I'd come to know best as the evil Visitor commander Steven from V, conveys a lot about his sharp-witted cop just through body language. Following the first crime, his anxious stance and wandering eyes betray how beyond his experience this incident is. Yet Ramsey keeps pace with Morales and the two make an effective team. Interestingly, Prine also takes credit for writing the film's exciting finale, in which Morales and Ramsay give chase to the Phantom Killer through a sand pit.

The liberal mixing of fact and fiction gives the story an added edge, particularly since (SPOILER), the Phantom Killer was never apprehended, leaving audiences of the period with the lingering question of whether the murderer was still out there, perhaps in the same auditorium as they were, watching his story unfold on the big screen. As such, The Town That Dreaded Sundown not only presages the questionable use of the 'based on true events' label for many modern horror films and the verisimilitude many found-footage flicks strive for, but also served as a model for higher-quality fact-based thrillers such as David Fincher's Zodiac, which features some very similar attack scenes and a similarly ambiguous resolution. A meta-sequel to the film is due out this month.

No comments:

Post a Comment