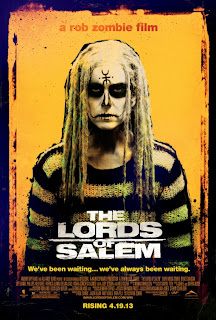

As a filmmaker, Rob Zombie is both extremely fascinating and incredibly frustrating. Thus far, his movies always seem to have fallen short of greatness but always show real potential, play with some interesting ideas and display a distinctive vision, albeit one laden with Zombie’s influences, mainly the horror films and music of the 60s and 70s that he grew up on. The landscape of his films is a grim, unforgiving place full of sudden violence, colorful profanity and little warmth or sympathy.

Each time he announces a project I’m interested, always

hoping this will be the one where he breaks out and creates the masterpiece he always

seems to be on the verge of. With The Lords of Salem, my interest was even

higher since the film was shot in my hometown. As Zombie, himself a

Massachusetts native, and company took over the streets, there was quite a buzz

around Salem. This is a city of rich history but conflicted identity that has been

defined primarily by the tragedy of the witch trials, a shameful event that has

nonetheless proved lucrative for the tourism it draws. Surely with such a

fascinating backdrop, Zombie’s newest production should be his masterpiece.

As the film ended, I initially concluded that Lords of Salem was a step backwards from his previous efforts, a scattershot pastiche of the Satanic thrillers of Zombie’s beloved era but with no soul of its own. However, the film got stuck in my head over the next few days and a new understanding of it emerged that makes me suspect that it’s a deviously brilliant, subversive film, although not necessarily a really satisfying one.

Zombie saves the real fun for the ladies, giving some good opportunities for

notable character actresses to pop up. These include Patricia Quinn, Judy

Geeson and the adorable Dee Wallace Stone as Heidi’s friendly but slightly

unnerving neighbors, lending some Rosemary’s Baby-style paranoia to the

proceedings. A quiet spot of tea between them and Davison makes for the film’s

most hilariously suspenseful scene. Meg Foster, she of the spooky pale eyes, also

pops up as the head of the coven.

As the film ended, I initially concluded that Lords of Salem was a step backwards from his previous efforts, a scattershot pastiche of the Satanic thrillers of Zombie’s beloved era but with no soul of its own. However, the film got stuck in my head over the next few days and a new understanding of it emerged that makes me suspect that it’s a deviously brilliant, subversive film, although not necessarily a really satisfying one.

As a Salem resident, it can be tricky to be objective, especially since immediately

Zombie toys with our local history, forgoing fact for the nether-history

of witchcraft as presented in cinema. The story posits that among the group of

innocent men and women wrongly convicted and condemned to death for witchcraft,

there was in fact a group of real witches, the cackling, depraved sort that

align right up with our cinematic perceptions. 17th century Salem reverend Jonathan Hawthorne

declares war on this coven and executes them via burning them to death. Besides

trashing any sense of historical accuracy (ask any Salem tour guide or shop

keeper where they burned the witches and see what reaction you get), this would

seem to present the same unpleasant implication as the laughable Nicolas Cage

vehicle Season of the Witch: that maybe the Puritans and the church had the right

idea all along in persecuting and executing all those men and women. Zombie’s

sly joke is already being set-up.

We cut to the present, where Salem disc jockey Heidi

LaRoq (Sheri Moon-Zombie) receives a mysterious package containing an

unmarked LP from a band called the Lords of Salem. Once she hears the

screeching tune on it, she is afflicted by gruesome flashbacks of the coven and

other disturbing visions. Played over the airwaves, it has an entrancing effect

on the city’s other female residents. Heidi also becomes aware of a strange presence

that has taken up residence in the supposedly vacant apartment down the hall

and which seems to have sinister intentions toward her. The witches’ curse on the

residents of Salem is finally coming to pass.

Zombie often seems to employ a more genre-specific version

of Tarantino’s M.O.: he repurposes the visual styles and conventions of the

movies he adored in his youth for his own aims. Sometimes it seems he’s just

out to offer audiences the same experiences he enjoyed when he first viewed

those films. Other times he uses them to conceal a deeper, disguised meaning, as

in The Devil’s Rejects, his love letter to grindhouse psycho-killer and road

movies of the 1970s that dared the audience to sympathize with a family of

maniacs.

For this film, his influences are most blatantly visual as

he abandons the comparative naturalism of Devil’s Rejects and his Halloween

remake for a fever dream style assembled from the Gothic tableaux of Mario

Bava, the rigid symmetry of Kubrick’s compositions and the hallucinogenic

montages of Ken Russell. While it’s all disquieting and disturbing with plenty

of gruesome and gooey sights to behold, it never really managed to shake me as

scary. Even Zombie’s shock scares seem mistimed and misdirected.

But just as I was typing out this review, ready to dismiss

it as a thin cover version of older, better scare flicks, the movie began to tease

its real identity: a clever satire clothed in the skins of Zombie’s cinematic

mentors. Beneath the tropes of the standard satanic thriller, Zombie has hidden

a social attack as stinging as that in Paul Verhoeven’s Starship Troopers. Unfortunately

it’s also about as dramatically uninvolving.

Clever part first: Zombie has given us a cautionary tale as devised

by the forces of repression. His gross misrepresentation of the witch trials is

just as ludicrous as the idea that simply listening to music can destroy

someone’s mind and soul. Thus, he draws parallels between the oppressive

Puritan mentality that rationalized the witch hunts as a quest to protect the flock from corruption and the oppressive crusade centuries later by political forces out to protect the youth of America from rock music by bands like Slayer and Iron

Maiden, music that supposedly contained Satanic messages and allegedly caused

suicides among its young listeners. Once you begin decoding Zombie’s gag, many

of what seem like flaws begin to seem like deliberate little touches. The chants

and spells of the witches for example, I had dismissed as ridiculous and

sounding like the overblown lyrics of heavy metal bands. Well played, sir.

The drawback about crafting such a satire is that often the

dramatic needs of the story are sacrificed in the name of the message. It’s

tricky to put together a film that works as insidious social commentary while

engaging as entertainment on the surface level. Starship Troopers may be a

clever indictment of fascism and propaganda, it’s not very engrossing on an

emotional level as a result. Similarly, as a horror movie, The Lords of Salem

is a bit of a letdown in that to make its satire work, the edges of the film

that would make it scary end up a bit blunted.

To illustrate, let’s look at the human center of The Lords

of Salem, Sheri Moon Zombie. Rob Zombie’s wife, collaborator, muse and object

of his visual fetishization, she has appeared in all of his films and gave a

surprisingly moving and tragic performance in his remake of Halloween. Here she’s

given less opportunity to impress, stuck playing a strange paradox of a person

who in no way resembles the real-world conception of a human being in how she lives

or interacts with others. There’s an infantilism about her style of dress and her

joking with her co-workers that suggest a woman whose emotional growth is

stunted. She lives in a fabulous apartment decorated with Georges

Méliès prints and her job with her fellow DJs seems to make a career of hanging

out. Despite being in her forties (which appropriately would have made her a teen during the

height of the satanic music scare), she seems to represent the aimless youth.

She lives the life most teens would probably imagine they would have as adults.

From a dramatic point-of-view, Heidi's total lack

of agency is frustrating. When the song on the record begins to push her

towards mental breakdown, she does nothing that a normal person might do, such

as visit a doctor, confide in her co-workers or even investigate the meaning of

what’s happening around her. She simply endures it and falls under its spell. This

seems integral to Zombie’s idea: after all, those who sought to censor mass

media usually do so in the name of protecting children with the implication

they are unable to think or act for themselves in that regard.

Heidi is also a recovering drug addict who is

pushed toward relapse, the second recent horror heroine thus afflicted

following the Evil Dead remake. Of course, youth falling prey to their vices is

standard for the genre, but here it reinforces Heidi’s symbolic value. Heidi

becomes the personification of the young flock that needs protecting from itself.

All of this is great fuel for the metaphor, but it makes her as impossible to connect with as

Verhoeven’s Aryan intergalactic stormtroopers.

There are some interesting ideas about gender

at work as well. Many historians read the witch trials as another example of

the established patriarchy cracking down on women who would not conform to

gender roles. The victimization of women in horror movies has also been decried

to a great degree. Here Zombie makes another connection. The

female characters with agency and drive are the depraved villains while Heidi’s

powerlessness conforms to conventions in the genre for heroines. Accordingly

there is usually a male character who attempts to rescue the heroine from peril,

here represented by Bruce Davison as a historian who slowly begins piecing

together what’s going on. However, since he’s a liberal intellectual who views

the Salem witch trials through the sane prism of history, the film’s intentionally

warped politics demand that he remain ineffectual. Brainy, soft guys like him

can’t stop the threat to our youth.

Zombie has a bad habit of filling the

supporting cast of his films with somewhat distracting cameos by horror

personalities, but it manages to work out ok here for the rest of the cast. Ken

Foree and Jeff Daniel Phillips are fine as Herman and Whitey, Heidi’s co-workers who,

like her, seem determined to hang onto to the chaotic fun of their youth. Whitey’s

unspoken feelings for Heidi in particular feel like the hopeless crush of an

awkward teen.

The Lords of Salem is not really very scary

in the conventional sense so if that’s what you’re looking for, you may walk

away shaking your head. For Zombie, the real horrors lie on the social and

political levels. Still, it’s a nice novelty to see someone shortchange the

visceral terrors in favor of intellectual ones. It’s not quite a masterpiece,

but there’s something to be said for consistency. Rob Zombie remains as

frustrating and fascinating as ever.

While watching this, I completely missed that Bruce Davidson played Reverend Parris in the 1996 version of "The Crucible." This was most definitely NOT a coincidence! Another clever 'trick' by Mr. Zombie, which I take to imply that there was more to the 'generational curse' than is stated on the face of the script. (I wonder if "Lords of Salem" could even be understood as an extension of an "alternate history" of the Salem Witch Trials germinating from Arthur Miller's play.)

ReplyDeleteOf further interest regarding local color: there is a reference to a theatre venue called the "Salem Palladium" in the movie. There is no Salem Palladium, but there is a Worcester Palladium in Rob Zombie's home town of Worcester, Massachusetts. And there is no rock radio station in Salem, Massachusetts, but WAAF of Worcester, Massachusetts is a hard-rock station with commercially-promoted DJs and a somewhat 'gonzo' format much like is portrayed in the film. So this version of 'Salem' blends some of Zombie's home town into its depiction.

Kudos also to Mr. Zombie for featuring the legendary weekly-alt newspaper the "Boston Phoenix" prominently, on the very eve of its printing demise.

Good catch. I totally missed that too and agree that can't be coincidental on Zombie's part.

DeleteIt's funny, as soon as the Palladium was mentioned I turned to my friend and joked "I didn't know we had one of those." I'm happy that Zombie saw fit to throw in little nods to his home and immortalize the late, lamented Phoenix, as well as a few Salem business that have already folded since he filmed here.