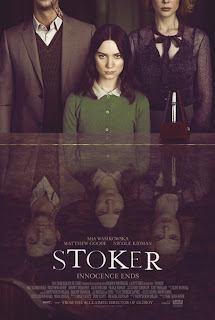

Fans of Korean director Park Chan-Wook, among whom I count myself, will know that he likes to focus on some grim themes, notably revenge, lust and other savage impulses that lie tucked away beneath one's civilized façade. For his English-language debut, Park is pleasantly on form with this Gothic suspense-drama that stylishly depicts how in some circumstances, no amount of family counseling can ever be enough.

The home dynamics of the family in question, consisting of the

introverted India Stoker (Mia Wasilkowska), her emotionally distant mother

Evelyn (Nicole Kidman), and loving father Richard (Dermot Mulroney), already

seem a bit abnormal when Richard is killed in a car accident on India’s

eighteenth birthday. One unexpected mourner at the funeral is Charlie (Matthew

Goode), Richard’s heretofore unknown brother who seems eager to have an

extended visit and grow close to his family, perhaps closer than is healthy. As

a flirty attraction growing between Evelyn and Richard, India becomes unnerved

by Richard’s attention and the conflicting emotions it stirs. Meanwhile the

disappearance of the family’s maid and foreboding hints from a nervous aunt (Jackie

Weaver) suggest a deep, dark family

secret is about to come to light.

The basic plot outline would suggest an interbreeding of

Hitchcock’s Shadow of a Doubt with a feminine take on Hamlet, but the

screenplay, by Prison Break star Wentworth Miller, takes a gradual curve into

something much more disturbing and interesting by upturning audience expectations regarding the characters and how we feel about them, or think we should. He also shows confidence in the

audience by allowing them to piece together or interpret some story elements

without too much comment or explanation. However, this ambiguity can be a bit

problematic in terms of plot logistics and character motivations. As the film

progresses, India begins making some decisions that don't always seem logical, or at least what normal people would consider logical. I also found myself pondering some murky plot points after the credits (which appropriately enough scroll in the wrong direction) wrapped, such as just who gives India an important object that becomes key in solving the mystery of her uncle, and why it was given to her.

Park’s visual style puts us squarely into India’s somewhat

unstable mind and insular environment, as the handsome cinematography ably

captures both the beauty and decay of the country setting in rich, dark colors. Tight close-ups visualize India’s skill at observing tiny

details while the use of sweeping camera moves imbue even quiet dinner scenes with a sinister energy

that delineates the battle lines between everyone seated at the table. When the violence comes,

as it must given Park’s preferred subject matter, it’s alternately presented in disturbingly erotic slow-motion close-ups or in clinically-detached wide shots that somehow enhance the horror of the moment

while cutting back on grisy detail.

The fractured editing neatly conveys how India processes events, with actions as mundane as opening a piano’s fall board triggering flashes of horror. There’s also a dynamic use of sound for both storytelling purposes, such as during a party scene where the whispers of bystanders gives us some key insights into India and Evelyn’s relationship, and for purely visceral ends, such as the disgustingly satisfying squish a blood-soaked pencil makes in a sharpener.

The fractured editing neatly conveys how India processes events, with actions as mundane as opening a piano’s fall board triggering flashes of horror. There’s also a dynamic use of sound for both storytelling purposes, such as during a party scene where the whispers of bystanders gives us some key insights into India and Evelyn’s relationship, and for purely visceral ends, such as the disgustingly satisfying squish a blood-soaked pencil makes in a sharpener.

Wasikowska has been proving herself to be as talented as she

is beautiful and anchors the film as our Goth girl heroine.

Introverted, antisocial and isolated, India spends much of the film observing

others, her hunter’s eyes peering out at the strange world around her from

beneath long dark tresses that frame her face like an iron helm. But where it

would be easy to substitute attitude for character in this kind of role,

Wasikowska makes us feel the turmoil and confusion beneath India’s stoic façade

as she struggles with her burgeoning sexuality, a turbulent period in any young

person’s life, much less someone facing it without motherly support and in the

creepy context India faces. The dynamic of Wasikowska’s previous roles in films

like Alice in Wonderland and The Kids Are Alright, in which young women pass

through strange events to emerge independent and better able to face life, is

deliciously corrupted here.

Goode has a tricky line to walk as Uncle Charlie, required

to present an outward plastic charm but with an undercurrent of menace that may

or may not be a result of India’s skewed perception. It’s to Goode’s credit

that when the mask is briefly lifted and we finally get a sense of his motivations and what his place in the family is, it feels consistent and is surprisingly affecting.

With Kidman as Evelyn, I admit initially I felt there was

something lacking, less from performance and more because on a script level it

seemed as some aspect of the character wasn’t fully explored or defined. On

reflection however, when one considers how much of the story we see from

India’s perspective, that may be the point. Like India, we feel it difficult to

relate to this seemingly shallow woman who displays little grief over her

husband’s passing. But as the story plays out, we begin to sense that her facile

socialite cheer conceals the deep loneliness, discomfort, and resentment of a woman trapped in a chilled

marriage.

There's a good chance Stoker is the type of film that divides audiences, as it could easily turn off people due to its midpoint surprises and its willingness to complicate audience identification with its heroine. But those with a taste for the demented and macabre, among whom I count myself, shouldn't hesitate to follow into the dark places it leads. Definitely recommended.

There's a good chance Stoker is the type of film that divides audiences, as it could easily turn off people due to its midpoint surprises and its willingness to complicate audience identification with its heroine. But those with a taste for the demented and macabre, among whom I count myself, shouldn't hesitate to follow into the dark places it leads. Definitely recommended.

No comments:

Post a Comment